Matthew Rolston: Talking Heads is a photographic project comprised of color portraits of a rare collection of ventriloquism dummies.

Essays

Bright Lights, Wide Eyes

There is nothing quite like the gasp that escapes your mouth as you walk through three small buildings on a quiet residential street in the small American town of Fort Mitchell, Kentucky, and find yourself mutely stared at by 1,400 eyes and grinned at by hundreds of painted lips over leathery chins. You are sharing company with beings barely this side of cartoon, bearing long proboscises or protruding goggle eyes, shapeless torsos and eerie charm. Lining the walls are photographs of these very figures perched on the knees or cradled against the shoulders of the men and women who once gave them voice: dummies and their ventriloquists.

Interior, Vent Haven Museum. Photograph by Edward Rothstein for The New York Times.

At the Vent Haven Museum the unsettling amazement is unremitting. In one room you almost feel as if you have bumbled onto a stage surrounded by a peculiar audience, each listener gawking in silence. In another the figures are arrayed in rows like Pinocchios who have finally made it to school.

Just as no two humans are smart in precisely the same way, no two of these creatures are dummies in precisely the same way. The gasps arise partly because you are overwhelmed by visceral sensations, the sheer accumulation of unexpected objects. The collection is the result of an obsession that wrenched these objects from their surroundings, in celebration of a craft.

The Vent Haven Museum grew out of the passion of William Shakespeare Berger, a Cincinnati businessman, who began accumulating the paraphernalia of the ventriloquist’s art in 1910. He later served as president of the International Brotherhood of Ventriloquists and before his death, in 1972, endowed this museum, which began in his own home.

The effect of the Vent Haven Museum is intensely personal. Its figures are silent objects constructed in order to give voice to—what? Walk among them though, and you can almost hear the nattering rustle of jests and jokes. Two heads from 1820s London, made with papier-mâché and glass eyes, have the intensity of fine sculpture.

The word “ventriloquist” comes from Latin roots alluding to speech from the belly—which means speech from anywhere but where we expect. The ability to throw one’s voice is cited by Hippocrates and alluded to in accounts of oracles. Cardinal Richelieu is said to have used a ventriloquist in 1624 to frighten one of his bishops. But it wasn’t until the latter part of the 19th century that the disembodied voice found a secure home in a puppet. Here it isn’t just the voice that is thrown; it is the imagination. Psychological realism generally trumps physical realism: the dummy gives voice to the psyche. It is really the dummy who vents, saying things the vent cannot. It is hard to imagine another place so clearly evoking the manifold powers and passions of the inner voice, simply by displaying figures who are its empty vessels—signs awaiting significance.

How else can you respond to silence so weighted with potential, except by producing an inarticulate cry? So we look. And we gasp.

Dummies’ Dreams Fulfilled

They stare at us expectantly, these dummies, as if awaiting a response. The inhabitants of the Vent Haven Museum regularly startle and impress visitors with their collective gaze. How to respond to such apparent yearning? Photographer Matthew Rolston succumbed to their silent pleas by making portraits of them. Each photograph is five feet by five feet in size, a larger-than-life square format of considerable significance. They are neither conventional vertical portraits nor horizontal still lifes, but an intentional combination of both. Rolston sees these ventriloquist’s dummies as subjects, their individual personalities revealed by their hair and eye color, eyebrows, the shape of their noses and mouths, even the size of their ears.

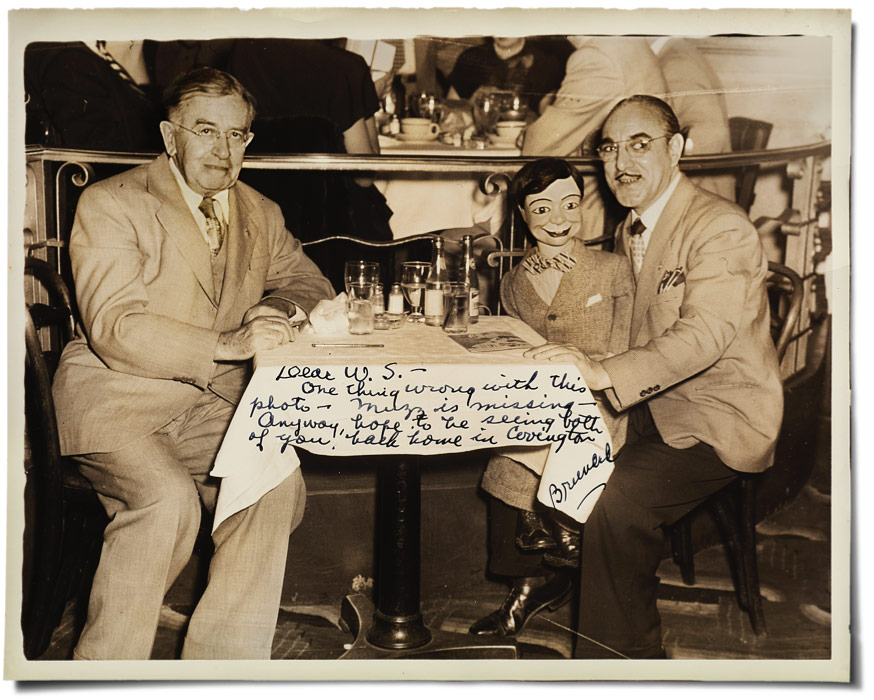

Vent Haven Museum founder W.S. Berger, left, dines with ventriloquist Dick Bruno and his figure, Joe Flip, at The Wivel restaurant, New York, late 1940s.

The same characteristics that fascinate Rolston when he photographs fashion models, celebrities and entertainers encouraged him to make the canny decision to depict these handcrafted performers as though they were living beings, which is not so hard to imagine. They spent their lives on the laps of the attentive but controlling partners who brought them into being, commissioning them from specialist figure makers to have eyes that could roll with exasperation, brows that could rise with surprise, ears that could wiggle in amusement, even the seeming ability to drink or smoke, just like their nightclub audiences. Some of them have traveled the world making people laugh, until they or their owners outlived their usefulness. In silent retirement, they perform no more. In Rolston’s portraits these ventriloquial figures, as they are termed, look improbably alive. He was moved to reanimate them through the alchemical medium of photography, choosing about two hundred of his subjects from the Vent Haven Museum collection of more than seven hundred figures, simply because he responded to their appearance, which could be striking, exotic, or disturbing.

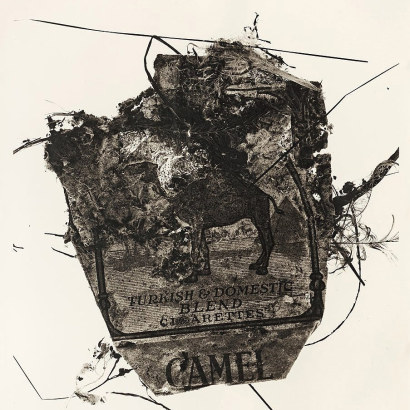

Certainly empathy was one reason that drove Rolston to expend the time and resources in pursuit of this project. He created these pictures for one of the defining reasons used by artists throughout history: he liked the way they looked and wanted to see if he could influence how they would be seen, how they could become part of the larger visual culture. An influence in this regard is undoubtedly the estimable Irving Penn. Penn was a legendary photographer of fashion models, statesmen, and entertainers, most often for Vogue. After thirty years in the trenches of beauty, however, he decided to assign himself the task of finding beauty in its opposite. He photographed cigarette butts and other garbage found in the gutter, and created exquisite platinum prints of generous scale. To many viewers they seemed ugly, revolting, especially in contrast to his life’s work in the glamour industry. For Penn, however, this late subject matter continued to be about abstract line, form, and rhythm in the photographic image. He seemed determined to prove that his art was the result of his talent and skill, as opposed to the inherent appeal of his models.

Penn’s subsequent subjects—flotsam and jetsam from the street as well as still lifes with animal skulls—all underscored the passage of time, issues of mortality that he finally chose to pursue as an artist. His highly detailed black-and-white photograph of a smashed pack of Camel cigarettes may seem casual, but it is an exacting composition, with stray bits of matter springing outward from the center. We see a parallel in Rolston’s photograph of Art Anteak, with his bulging eyes, his nose and mouth scraped and mashed, anarchic injuries that may have come from being abandoned. The roughened surface textures and the strands of hair sticking out this way and that recall the controlled chaos of Penn’s composition.

Irving Penn, Camel Pack, 1975.

Matthew Rolston, Art Anteak, 2010.

Rolston, too, has chosen subjects that are no longer beautiful or pristine, a kind of cultural detritus with little obvious value. We see in his pictures the toll taken by passing years: the flaking of painted makeup, the sometimes-improvised repairs, the loss of hair, the sagging of the leather skin used around the mouth.

Rolston asked Vent Haven curator Jennifer Dawson to hold each figure in front of a white backdrop that was lit by a single hard light source. He positioned the camera to capture the glint of light in the dummies’ eyes, lending each one the appearance of being interested or attentive, as though listening instead of speaking. Using a wide-angle lens to accentuate facial features, Rolston took each photograph from a slightly low angle to emphasize monumentality. We are virtually forced into the compositions, since many of the heads are cropped across the top, a device used to great effect by Richard Avedon and Irving Penn. These photographers were early influences on Rolston, who grew up looking at images by them in the glossy pages of his mother’s Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar magazines.

Andy Warhol, Turquoise Marilyn, 1962.

Matthew Rolston, Powers Girl, 2010.

The tightly cropped face was used as well by Andy Warhol, who gave Rolston his first break, asking him to photograph Steven Speilberg for Interview magazine. Warhol remained a guiding light, and the square format of his celebrity portraits surely influenced Rolston’s choice for this work. Compare Warhol’s silkscreen portrait of Marilyn Monroe with Rolston’s Powers Girl, both with slashes of pale blue eye shadow. In acknowledgment of the iconic Warhol painting, Rolston closely cropped Powers Girl, cutting off the top of her blonde hair and eliminating her shoulders, isolating the mask of the face. The barely visible green scarf around her neck is nearly the same shade as the background of the Marilyn image. However, the googly eyes of the dummy lend it both a comic and tragic air.

If photography has the ability to freeze life as it once was, Rolston’s work here has another purpose: to suggest life lived once more. This is a departure from the ways in which puppets, mannequins, dolls, and dummies are typically depicted. Hans Bellmer’s early twentieth-century photographs come to mind, dismembered surrogates of female bodies that had a strong connection to the surrealist aesthetic of that time.

Vajrasattva mandala, Tibetan, seventeenth century.

Matthew Rolston, Barnaby, 2010.

These dummies appear bizarre, certainly, but not surreal. Rolston has photographed them with compassion, the way a child gives a name and a personality to a doll or stuffed animal. Rolston has tapped into a universal impulse to project our own human qualities onto inanimate figures. (Think of The Velveteen Rabbit, Pinocchio, even Toy Story.) Barnaby, for instance, with his natty striped suit, raised eyebrows and wide sunburst eyes, has an hypnotic quality suggestive of a Hindu or Buddhist mandala, with its ability to draw a viewer into its contemplative presence. The circle-in-the-square format of this spiritual diagram is echoed by the circular head and eyes within the four equal sides of Rolston’s composition.

We recognize these creatures as familiar; we are drawn to them and their stories as we are drawn to one another, with pathos and humor. Like their human creators, they embody individual personal histories that provoke our curiosity, even our identification. Rolston is not the first photographer to document these dummies: Artist Laurie Simmons took photographs at the Vent Haven Museum in the late 1980s, though Rolston was unaware of them until after his own project had been completed. Simmons called her series Talking Objects and posed the dummies as curiosities in context, objects with in a still life. By contrast, Rolston sees them as subjects, not objects. That crucial distinction informs his decision to use a radically simplified format.The identical frontal pose, without background or props, insists on their status as portraits of individuals. We cannot escape their eyes. In these extraordinary photographs they appear to us as entertainers who have been brought out of retirement for one last show. We imagine their pride and elation as they face a new audience.

Talking Heads

If masks are, as Spanish philosopher and poet George Santayana wrote in the early 1920s, “arrested expressions and admirable echoes of feeling” then the Vent Haven Museum in Fort Mitchell, Kentucky, must contain one of the world’s more unique and evocative collections. It is a place like no other.

After discovering Vent Haven through an article by Edward Rothstein that appeared in the New York Times in June 2009, I became deeply intrigued by its inhabitants. I knew nothing of ventriloquism then, and still know very little, but I have learned of the poetry of these figures and the ways in which they were brought to life as an expression of their creators— the figure-makers and ventriloquists.

I began by approaching my subjects because of how they look, not necessarily because of their historic or cultural value.The faces that spoke to me most had expressions that I found enigmatic, pleading, Sphinx-like, hilarious, and disturbing—all at once. To me, the greatest portraits are mostly about finding a connection with the subject’s eyes. There’s an expression of yearning and desire in these eyes that I find disturbing.

Matthew Rolston, Joe Flip, from the series “Talking Heads.”

Ventriloquism has ancient roots. Long before the music hall era, before vaudeville, radio, or television even existed, there was shamanism and there was ritual. When the shaman spoke to the tribe, channeling the voices of spirits—sometimes animist, sometimes divine —no doubt he or she used the same techniques as those used by modern ventriloquists. All forms of modern entertainment and storytelling come from the same primal beginnings.

What makes ventriloquism as an art form and culture all the more fascinating is that it embodies the “god complex.” A man (or a woman) gives birth to a lifelike, moving, speaking facsimile of another human. This is both primitive and miraculous. In performance, the ventriloquist literally has a hand inside the figure’s body and head, making it appear alive.

The dummies have moving parts: mouths of course, but eyes that can roll, eyebrows that can rise and fall in surprise, heads that turn, and sometimes more. They’re not puppets. There are no strings to animate them, they appear to move and speak—often mocking their creators (or some social convention)—and they seem to be as smart as their creators, in fact, usually smarter.

The bond shared by the human and their wondrous creation is the part of ventriloquism I find most gripping. It’s the space between. Just as in a classic two-man comedy act, a ventriloquist and his or her dummy are partners—each other’s yin and yang. It’s always a give-and-take. After all, what’s a joke without a punch line?

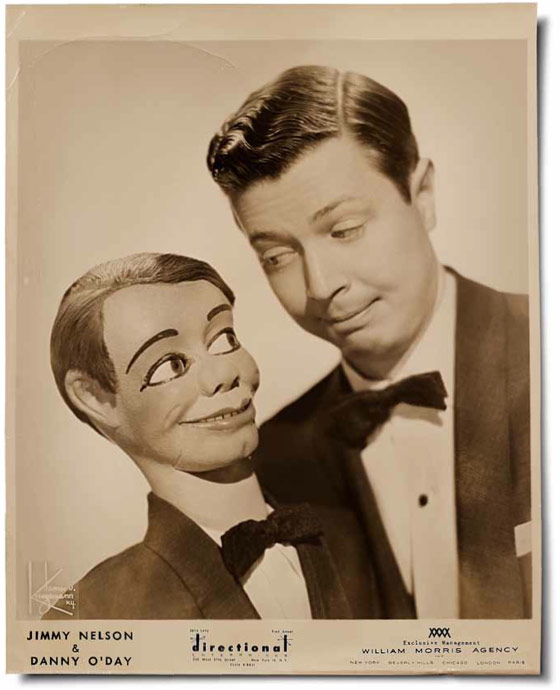

Ventriloquist Jimmy Nelson posed with his figure, Danny O’Day, for a promotional photograph around 1950.

What time has wrought on the figures speaks volumes, in a language both satirical and tender. Their expressions evoke a sense of serenity, a melancholy that suggests a spiritual longing, authentically embodying three telling truths: nothing is perfect, nothing is ever finished, and nothing lasts.

Perhaps in their solitude today, separated from their makers, they represent a liberation from our materialistic world. No longer aided by the human voices that once spoke so magically through them, the Vent Haven figures now speak by the simple fact of their physical presence. To paraphrase American poet Helen Hay Whitney: these old lost stars rise and gleam once more. The dummies don’t just channel humanity, they fetishize it. Human history is all over them. They are overwhelmingly, intensely human objects. They are my subjects.

I See History

Holding this book in my hands, gazing at the pictures of ventriloquist figures from long ago, I don’t see cracked faces and peeling paint, I see history. No, that doesn’t describe it properly: I experience history. Contemplating Matthew Rolston’s portraits reminds me of the first time I set foot in the Vent Haven Museum in Fort Mitchell, Kentucky. I was not prepared for the enormity of emotions I would experience upon seeing the puppets from several generations of ventriloquists. My feeling had always been that it would be a nice novelty, something that would be forgotten quickly, but I was immediately struck by how amazing it was to stand in a place with such a palpable sense of the past.

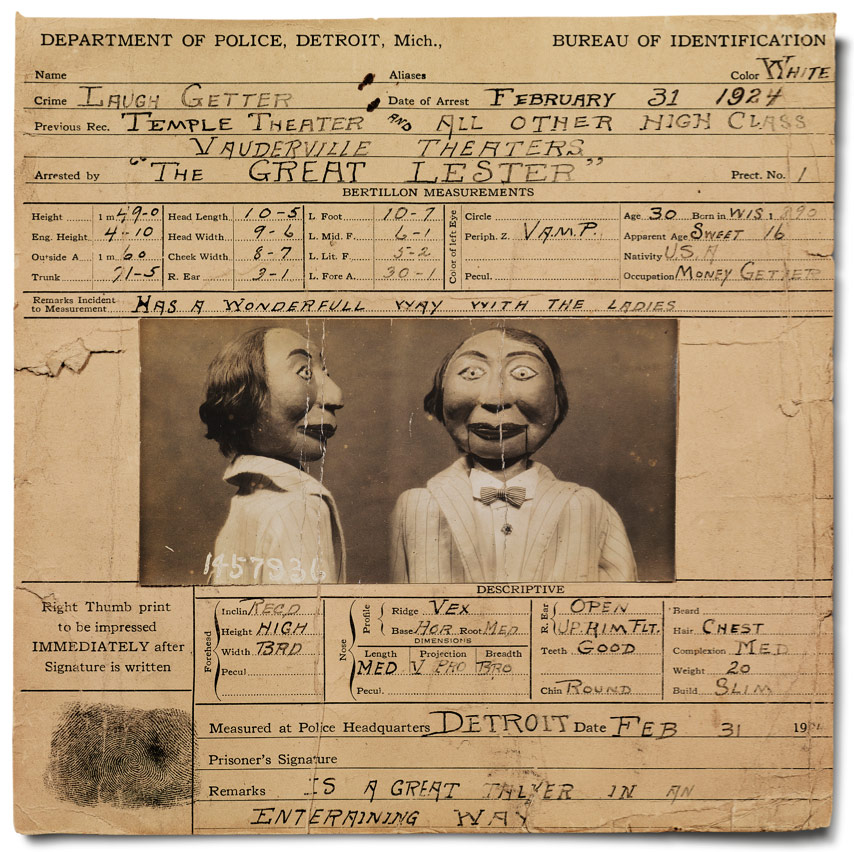

This one-of-a-kind “mug shot” promotional card was created for an appearance by the Great Lester at the Temple Theater in Detroit, Michigan, in 1924.

Wandering through the museum, gazing at the puppets of my heroes—Edgar Bergen, Paul Winchell, Jimmy Nelson, and many others— I could grasp the story of each character I was viewing. As I looked at Charlie McCarthy and Mortimer Snerd, I closed my eyes and imagined myself being at one of those 1930s radio broadcasts, watching the live show that was being aired throughout the country. My mind drifted to the family listening to that show together in their living room.

I could almost smell the traces of a home-cooked meal already eaten, on those Sunday evenings as the family gathered eagerly around the radio to listen to their after-dinner entertainment. Who would be the guest star tonight? Marilyn Monroe? Roy Rogers? Last week W.C. Fields and Charlie’s bantering had the family laughing so hard the kids were rolling around on the floor!

Snapping out of my reverie, I continued to find myself gazing at Jimmy Nelson’s ‘Farfel.’

Again I was transported to another time. I closed my eyes and beheld the stage of the Texaco Star Theater and its host, Milton Berle. I could see Jimmy Nelson striding onstage in his Texaco gas jockey uniform, with Danny O’Day. I wondered if he was nervous or confident, or perhaps a mixture of the two?

I flashed forward and saw millions of children watching Farfel the Dog cry in his sing-songy bass drawl,“CHOC’-LATE!” Once more I was brought back into the present as I opened my eyes.

I had a similar experience as I viewed the Paul Winchell display, reliving his moments as a top children’s television star; he created entirely new puppeteering techniques that are still unparalleled today.

It would be easy to just dismiss such a feeling and not allow one’s imagination to return to the glory days, but alas, that’s not who I am. One of my favorite displays at Vent Haven is a group of puppets that had washed up on the shore after a shipwreck.

Closing my eyes, I envisioned a splendid cruise ship with fancy dining utensils and polished brass handrails.

I imagined the handsome ship-board showroom where audiences laughed and cheered the ventriloquist as he expertly entertained them with the illusion of creating life from wood and fabric.

Then I saw the lonely puppets washing onto a shore where they were found and later displayed in a small museum in Kentucky. The Vent Haven Museum is a place where anyone can be drawn into the worlds of past glories and the entertainers of yesteryear, and I highly recommend it. But until you get the chance to go in person, this book is definitely the next best thing to being there! Let your imagination run free and enjoy the past.